Evangelina Mascardi - Projects

Evangelina's Lutebook

In this programme Evangelina Mascardi draws together different works from various Italian, French and English manuscripts and publications from the XVI century and creates an intimate fresco which reflects, through the peculiar stylistic forms of lute Renaissance repertoire, the innovative blossoming of contemporary figurative arts.

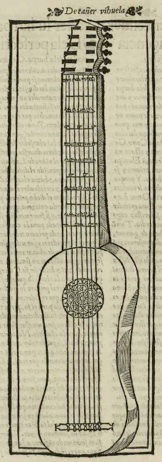

The lutenist is a very fortunate instrumentalist. We could say that we have “only” 250 years of specific repertoire, from the first printed edition Intabolatura de lauto libro IV by Joan Ambrosio Dalza, published in Venice in 1508 by Ottaviano Petrucci until the death of the last of the great lutenists, Sylvius Leopold Weiss, which, in 1750, marked the sunset of this extraordinary journey.

The lutenist is a very fortunate instrumentalist. We could say that we have “only” 250 years of specific repertoire, from the first printed edition Intabolatura de lauto libro IV by Joan Ambrosio Dalza, published in Venice in 1508 by Ottaviano Petrucci until the death of the last of the great lutenists, Sylvius Leopold Weiss, which, in 1750, marked the sunset of this extraordinary journey.

It may be argued that it is a short period compared to the historical course of other instruments, in particular, the Strings. But it is undeniable that the quality of composition is very high. We are looking at veritable musical monuments in which the lutenist composers were often prescient pioneers of what was to come in terms of style and the development of the instruments potential. If the works of figurative art of the Renaissance "played", they would sound like fantasies for the lute.

My recital presents and interweaves some of these masterpieces, taken from various Italian, French and English manuscripts and publications from the sixteenth century. I have been inspired by many Renaissance individuals - students, doctors, singers, lute players - who had their own manuscript collection, which was gradually enriched thanks to travelling, meeting new people, and exchanging music. It was actually as a result of the many copies made, for different purposes, by the simply curious, by the "amateur" musician, or by the court or palace copyist, that music had such wide circulation at that time. From each of these collections we can understand the technical level of its owner, his cultural context, which of the forms in vogue at the time he preferred (dances, fantasies, madrigal tablatures), his comings and goings, whether he also sang or used to accompany himself on the lute, or if he sometimes composed verses for pleasure, or, even perhaps wrote down his personal spending accounts.

Similarly, my notebook is my private collection, and says something about me, about my most intimate universe which in turn is mirrored by my desk covered with books for the lute open in the

search for that missing piece that would complete the Renaissance architecture of the program that I invite you to listen to.

Evangelina Mascardi, January 2016

Anonimo, A Robin

Alfonso Ferrabosco (1543-1588), Fantasia

John Dowland (1563-1626), Gagliarda Dulandi

Marco dall'Aquila, Ricercare

Joan Ambrosio Dalza (?-1508), Poi che volse la mia stella

Melchior Neusidler (1531-1591), Passamezzo

Anonimo, Branle

Albert de Rippe, Fantasia

Marco dall'Aquila (ca.1480-ca.1538), Ricercare

Anonimo, Saltarello bel fiore al mio modo

Albert de Rippe (ca.1500-1551), O Passi sparsi

Francesco da Milano (1497-1543), La Spagna

Albert de Rippe, Ave Maria Santissima

Anonimo, Il peschatore che va cantando

Albert de Rippe, Gagliarda

Simon Gintzler (ca.1490-1550), Ricercare

Claudin de Sermisy (ca.1490-1562), Tant que vivray

Luys de Narvaez (ca.1500-1560), Fantasia

Albert de Rippe, Chanson alla francese

Vincenzo Capirola (1474-1548), Padovana descorda

Evangelina Mascardi - Renaissance lute

Cesar Mateus, New Jersey, 2013